|

Introduction

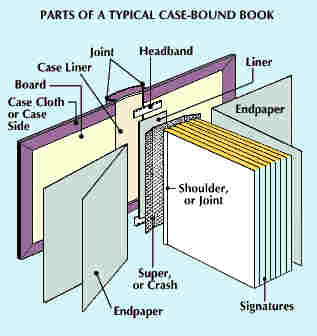

Parts of a Typical Case-Bound Book

The processes of binding a book by hand are much

the same as they were 500 years ago. Bookbinding began when the codex started to

replace the roll. The earliest elaborately decorated book bindings were those

produced for use on church altars. Those that survive are often magnificent

examples of the jeweller's, goldsmith's, ivory carver's, or embroiderer's arts.

The necessary equipment includes a sewing frame to

hold the folded sheets while the sections are being sewed to the cords or tapes

that run across the back. Also needed are two presses. The first holds the book

while the back is rounded by gentle hammer taps. The second holds it while the

covers are put on. In hand binding, unlike machine or case binding, the sewing

cords are fastened directly to the stiff board sides before the cloth or leather

covering is put on.

Contents

Back to Top

Decorated Covers

For decorating and lettering the cover of a book,

small brass stamps set in wooden handles are used. A wheel called a fillet makes

plain lines. Wider wheels, called rolls, with various patterns on the edges, are

used for producing and imprinting detailed ornamental bands or borders. In

gilding the edges of a book the first step is usually to spread a thick red

stain. After this is dry and carefully brushed, the binder applies a glair, made

of whites of eggs beaten up with water or vinegar. Then very thin gold leaf is

laid on. When the glair is quite dry and the gold has set, the edge is burnished

by rubbing with a smooth piece of stone or leather. Sometimes landscapes are

painted on the fore edge in such a way that they are only visible when the edges

are slightly fanned.

Although the processes of hand binding have

remained the same for centuries, there have been great changes in the materials

used and in the style of decoration. The earliest bindings, even for small

books, were usually made of oak boards. Sometimes the boards were covered with

leather or vellum; these are called full bound.

Sometimes the boards were left exposed, only enough

of the leather or vellum back being fastened to the edges to hold the sides;

these are called half bound. The ornamentation of the back and sides became a

special art, called finishing.

Back to Contents

Back to Top

Use of Paper and Cloth

As the production of books increased and the size

of the volumes decreased, bookbinders began to substitute paperboard for oak.

About the beginning of the 19th century glazed calico was first tried as a cover

for the paperboards, and about 1830 cotton cloth was introduced in England.

The use of cloth created new possibilities in

decorative binding. Cloth is more easily handled than leather or vellum and is

easily marked by stamps or dies. It permits binding large editions in identical

designs at low cost. In the United States and Great Britain, the boards of most

new books are covered with cloth, paper, or a combination of the two. In

continental Europe many books are issued in flexible paper covers. Permanent

bindings are put on later.

As early as the 4th century many manuscript volumes

were elaborately bound. Most of these, however, were later destroyed for the

gold, silver, gems, or carved ivory with which they were ornamented.

At first the printing and binding of books centred

in monasteries and church schools. Then it was transferred to universities and

later to commercial establishments. By the end of the 15th century a few

bindings were stamped with the names or devices of printers or binders. Some

early printers, notably Anton Koberger at Nuremberg, Germany, developed styles

of binding still associated with their names. Most binding styles are named

either after a binder or after a famous collector or patron.

Back to Contents

Back to Top

Gilded Decoration

A great variety of decoration was made possible by

the introduction of gilding, about the last quarter of the 15th century. In

Germany blind stamping (that is, without gilding) remained the fashion even into

the 1700s. In Italy, in France, and in some English binderies, leather stamped

in gilt became the material for fine bindings. In France, through nearly three

centuries, the art of binding received magnificent support from kings, queens,

nobles, and clergy. Their favourite books have since become the pride of

museums, libraries, and private collectors. Jean Grolier was one of the greatest

book collectors of the 1500s. Most of his books were bound in leather covered

with geometric patterns inlaid with contrasting bits of leather or coloured

enamels. Maioli bindings, made for Thomas Mahieu, secretary to Catherine de'

Medici, and the English bindings made for Sir Thomas Wotton are similar to the

Grolier books. The royal binders Nicolas and Clovis Eve, the unknown binder

known as Le Gascon, and later Antoine Michel Padeloup and Nicolas-Denis Derome

each developed definite styles of decoration. In mechanical finish the work of

these early binders is often inferior to that of the best workmanship of today.

In design it has not been surpassed.

In England in the 1600s, Samuel and Charles Mearne

developed the "cottage" style of decoration. This took its name from a

roof like pattern used in almost every binding. After the Mearnes there was no

important English binder until Roger Payne, one of the truly great binders.

Payne combined small patterns with pleasing blank spaces. Payne's designs were

more or less followed in the 1800s by Charles Lewis, Charles Kalthoeber, Francis

Bedford, and later on a greater commercial scale by the firms of Robert Riviere

and Joseph Zaehnsdorf. John Edwards of Halifax developed an original style,

usually called Etruscan from the patterns he used. Edwards made a specialty of a

transparent vellum. The underside of the vellum was decorated with landscapes or

allegorical painting. He excelled in fore-edge painting. His work is now highly

prized.

Back to Contents

Back to Top

Modern Designs

Design in bookbinding received a new inspiration

toward the end of the 1800s. This came at the same time as the artistic revival

in printing for which William Morris was responsible. Morris' friend Thomas J.

Cobden-Sanderson designed bindings which combined geometric figures with

conventional patterns. Cobden-Sanderson was one of the few hand binders who

himself did the finishing and all the sewing and forwarding. Cobden-Sanderson's

influence was great, through his own work and through his pupils. Among them

were Douglas Cockerell and Sarah T. Prideaux. In the United States most of the

outstanding binders, such as William Matthews and Alfred de Sauty, were men who

were born and trained abroad. They brought to this country the best European

traditions and standards of workmanship.

With the turn of the 20th century the note of

modernism appeared in binding design as in other forms of decorative art. Design

in binding follows the general trend of other arts. Modernism in binding is

comparable to the same trend in furniture or in architecture. Bookbinding is one

of the fine arts. Like all arts it reflects the spirit of its time.

Back to Contents

Back to Top

Book Manufacturing Today

The process begins with the decision of a publisher

to issue a book. After the manuscript of the book has been prepared, a book

designer, in consultation with editors and printers, develops specifications for

the book--its size and shape, the typefaces in which it is to be set, and the

treatment of tables and illustrations. The printer and the binder then prepare a

dummy, or mock-up, of the book, showing the paper to be used, the thickness and

binding of the volume, and--ordinarily--some specimen printed pages.

Back to Contents

Back to Top

Typesetting and Printing

After a book manuscript is edited, the next step is

to set it in type. Most books are typeset using phototypesetting machines. The

earliest models of these machines worked by taking a separate picture of each

letter in its proper place. Newer models use computer devices to store the

proper shape of each character as digital information.

This information is used to operate a cathode-ray tube (CRT), or a laser, which

forms the characters as needed. These more advanced

phototypesetters are also known as digital typesetters.

Phototypesetting machines use computer technology

to make typesetting much faster and simpler than the older hot metal techniques

of Linotype and Monotype machines. Before

actually setting the type, the phototypesetter rearranges the lines

electronically in order to produce justified copy (copy that is even at both

margins). When a word must be split, the machine indicates this to the operator,

who must tell the machine where to split the word. Larger, more modern

typesetting machines are capable of storing entire dictionaries in their

memories. This permits the machine to automatically split words at the proper

places and to check for spelling errors.

There are four kinds of phototypesetters:

photo/optic, photo/scan, digital/CRT/scan, and laser/scan. The first two employ

film grids that contain pictures of all the characters of a type font. In the

photo/optic typesetters, the film grid is positioned so that a light beam passes

through the correct character and is reflected onto photosensitive paper or

film. Lenses and mirrors can enlarge or reduce the size of the letter.

In the faster photo/scan typesetters, the film grid

is scanned electronically to form an image on a small CRT, which produces the

image that is reflected onto the paper or film. Since the characters are

generated electronically, they can be modified easily to make them slanted,

condensed, or heavier, as well as larger or smaller.

Digital/CRT/scan typesetters and laser/scan

typesetters do not use film grids. Instead, the typefaces are stored digitally

in a computer memory. In the digital/CRT/scan typesetters, the digital

information is used to generate a picture on a CRT of each character as it is

needed. This picture is then used much as in the photo/scan typesetters. The

laser/scan typesetter uses the digital information to control a laser, which

scans the photosensitive paper or film directly, exposing only those parts of

the paper necessary to form the words on the page. Grid-type phototypesetting

machines can set up to 50 lines per minute, while digital typesetting machines

can set up to 3,000 lines.

Although copy is usually typed into a

phototypesetter much as it would be typed on a typewriter, modern computers and

word processors also can be used to transfer already recorded information

directly for typesetting. This permits greater efficiency because the text need

be typed only once. Optical character readers (OCR's) have been developed that

can read text typewritten on ordinary paper. They store this information in

memory or transmit it to word processors or to phototypesetters.

Once the book's text has been typeset, it must be

proofread for errors. Most of the modern typesetting machines permit easy

editing and corrections of the text on video-display screens. Some machines can

display the text in precisely the form in which it will appear on the final

printed page.

After the text has been corrected, the type and any

illustrations are arranged in page format. These pages are photographed to make

the printing plates. Some phototypesetters can arrange the text into pages

automatically, allowing editors to review them on a screen before the type is

actually set. Other phototypesetters can also make the printing plates directly

from the information stored in memory.

Electronic engravers are often used in making the

printing plates for illustrations. Colour illustrations pose an added problem.

Since they are usually printed as four separate colours, one atop the other,

four separate printing plates must be made. This process has been much

simplified by the development of electronic colour scanners that can separate

the colours and make the plates in one operation.

Most books are now printed by a process known as

photolithography, more commonly called offset printing. Many books are still

printed by the older letterpress process or the gravure process. Sheet fed

presses, which print one sheet of paper at a time, have been largely replaced by

web presses, which use rolls of paper. The web-press operation permits faster

production by combining printing and folding into a single, continuous

operation.

Although the pages follow one another in numerical

order in a completed book, they are not printed that way. Each printing plate

contains a number of pages, so positioned that they will fall in proper order

when the unit of pages, or signature, is folded. Signatures may contain any

multiple of four pages; common signature sizes are 16, 32, or 64 pages. Most

presses print both sides of the paper at once and deliver folded signatures,

ready for the bindery.

Back to Contents

Back to Top

Elements of Modern Bookbinding

Essentially, the steps in edition binding--or case

binding, as the mechanized process is called--are the same as those in hand

binding. The signatures of the book are put in proper order, fastened together,

and enclosed in a protective cover. In assembling the book, those operations

which take place before the signatures, or body of the book, are joined into a

unit are called sheetwork; those which take place afterward are called

forwarding.

Steps in sheet work include folding the signatures

if they were not folded on the press, arranging them in order, and fastening

them together. Signatures are put in order on a gathering machine, or gathering

line. Piles of successive signatures are arranged in order in bins beside a

conveyor belt. A mechanical arm takes a first signature from its pile and places

it on the belt. The belt carries the signature to the next position, where

another arm places a second signature on top of it. The process continues until,

at the end of the line, a complete set of all the signatures in the book has

been assembled in the correct order.

Next the signatures are fastened together. Three

processes are in common use. Probably a majority of all books, and certainly

most general, or trade, books, are flexible sewn. The process is also called

Smyth sewing, after David McConnell Smyth, inventor of the first flexible-sewing

machine.

In flexible sewing, each signature is sewn through

its binding fold (the fold at the back, or spine, of the book) and to the

adjacent signatures. Flexible-sewn books open easily and the pages lie flat.

After the signatures are sewn together, the endpapers, which help hold the book

in its cover, are tipped to the first and last signatures with thin lines of

glue applied near the binding fold.

The book then passes to the nipper-gluer, in which

the backbone is compressed to reduce the bulk created by the sewing thread and a

coat of glue is applied to the spine to further bind the signatures together.

Some books require overall smashing, instead of just backbone nipping, to reduce

excess bulk.

Now a unit, the signatures are trimmed to final

size by heavy knives. Then, in the rounder-backer, the backbone of the book is

rounded to help the book hold its shape, and the joint, or shoulder, in which

the cover boards will hinge is formed. If desired, gilding--usually of

artificial gold--or stain is applied to the top of the book.

Then the super, or crash, is applied to the spine

of the book. This strip of open-mesh fabric, easily penetrated by glue, extends

beyond the edges of the backbone. Later it is glued to the cover boards beneath

the endpapers, helping to hold the book within its covers. A paper liner is

applied over the super, and decorative headbands are glued to the spine. The

book is ready for its cover.

Book covers, or cases, are prepared on case making

machines in which the boards and case liner are glued to the covering cloth

(case cloth, or case side). Decoration--the book's title, author, and publisher,

together with any desired illustration--may be applied to the case side either

by printing, before the case is assembled, or by stamping--usually in artificial

gold foil--after assembly.

The book and its cover are brought together at the

casing-in machine. Here glue is applied to the endpapers, and the super and

endpapers are glued to the boards and sealed under heat and pressure. Other

machines wrap the book's dust jacket around it and, if desired, put the book

into an individual carton and address it for mailing.

The development of fast-drying inks and

fast-setting glues, largely since the 1950s, has brought to edition binding a

speed and efficiency undreamed of in earlier years. Formerly, long waiting

periods between binding steps were necessary to permit adhesives to cure. Today,

a book may proceed from a stack of loose signatures to a fully bound volume,

wrapped and addressed to its buyer, in a matter of minutes. For long-run

books--volumes of which many thousands are printed--highly automated production

lines may be built. In these, books are mechanically bound with little or no

human attention.

Back to Contents

Back to Top

Side-Sewing and Adhesive Binding

Although there are several means of reinforcing a

flexible-sewn book so that it can withstand harder than ordinary usage, most

books intended for heavy use--such as textbooks and encyclopaedias--are fastened

by the process of side-sewing or side stitching or both. (In bindery terms,

"sew" indicates the use of thread; "stitch," the use of

wire.) In side-sewing and side stitching the gathered signatures are simply sewn

straight through, from one side of the book to the other, near the binding fold.

When a book is side-sewn, the endpapers are tipped to narrow strips of drill

cloth. These strips are sewn together with the signatures. A side sewn book

ordinarily has no super, since the function of the super is performed by the

drill strips.

Adhesive binding, which is becoming more and more

common, was made possible by the development of fast-setting glues which retain

flexibility even when dry. In this process the gathered signatures are pressed

together between jaws and the binding folds are cut off, exposing an edge of

each leaf. The edge is roughened, and a coating of glue is applied to hold the

leaves together. If an adhesive-bound book is to be cased in, endpapers are

tipped to its spine and a super is applied. If it is to be soft bound, or

paperback, the same glue that holds the leaves together attaches the paper cover

to the spine, and the book is completed by trimming pages and cover at once.

After sewing or gluing the remaining steps in casing-in side-sewn or

adhesive-bound books parallel those required in casing-in flexible-sewn books.

Back to Contents

Back to Top

|